Affordances in Time – The progress of Dr. Eóin Phillips’s research in GREITM

The evolution of his work from his previous GREITM’s research seminar

Dr. Phillips gave an account of the process through which mechanical timekeepers came to be used on voyages at sea. According to traditional scholarship - and, more importantly, a film and best-selling book (!) – timekeepers (a type of clock which came to be known in English as chronometers) were crucial instruments for European navigators to know both where on the globe they were and to know precisely in which direction they should travel.

This navigational potential was based on a system in which knowing both the time of where the ship had left (home) and the time at which the ship currently was could give you an east-west coordinate, known as longitude. One degree of longitude was equal to 15 minutes difference in time between the time of the ship and the time it currently was at ‘home’. To know the time of the place at which the ship was currently in was a fairly simple astronomical task for sailors. To know the time of somewhere where the ship was not was a much more difficult task. Timekeepers, it was hoped could ‘keep’ the time of the home destination.

Without these mechanical instruments, the traditional scholarship suggests, the risk of European ships being lost and shipwrecked was simply too great. As the foundation of European trade, imperialism and warfare, the need to prevent losing ships to poor navigation was seen by the European political establishment as one of the major technical and scientific tasks of the day.

With precision clocks as the solution, it is not too extreme of a summary to say that according to traditional accounts, without navigational clocks, the whole course of European and even history would have been profoundly different.

In his talk, he argued that this type of account is an example of what sociologists and historians of science and technology call ‘technological determinism’ – that is, the idea that technologies exert a profound force on the social structure in which they are introduced.

Instead, Dr. Phillips argued that the traditional accounts of mechanical timekeepers on European ships profoundly misunderstood their role and purpose.

Where these accounts claimed that mechanical clocks were necessary for European sailors to know where to go to find their longitude, he showed how in fact clocks were only navigationally necessary at two key points on trans-oceanic voyages: when to south in the Atlantic and when to turn North after rounding the Cape of Good Hope to catch the trade winds and monsoon season respectively, to carry ships Northwards into the Indian Ocean.

By missing the moment to capture these winds, ships could be delayed from returning to Europe with their expensive cargos of goods or soldiers, which could result in a massive commercial or military loss for the investors in that ship (either the trading company or the state). Delays in cargo or crew could be near-fatal for their backers.

In the talk to GREITM, he showed how that when ship arrived back the metropole late, the boat’s officers would be asked to account for why such a delay in time had occurred. Due to the fact that from the eighteenth to the late twentieth century there were nothing like modern surveillance devices, a ship’s officers were told that their most trusted evidence would be from submission of their routes and journals based upon their measurements of longitude by timekeepers and other astronomical methods. These collections were called ‘logs’. Importantly, the reason for making these logs were not to prevent shipwrecks, but rather to show how and why a ship had taken the route that it had.

If a ship was found to be late due to the poor evidence from the records, then a ship’s captain would be subject to potential punishment, due to the commercial and/or military risk involved.

Precision instruments like mechanical timekeepers, therefore, were much less about getting things to go where they had to, but much more about providing some way to gauge failure when they did not.

In this way, he showed how mechanical timekeepers should be thought of as less a strictly navigational tool, but much more as a retrospective management device: by focusing on the social rather than simply the technical aspects of technology, Dr. Phillips suggested that our understanding of technology in the world may be significantly shifted.

The connection of his research with the “Quantum Revolution”

During his time working to understand the function of navigational technologies in the 18th and 19th centuries, he has also been encouraged at La Salle to begin looking at the development and potential impact of a very different set of technologies being developed in the twenty-first century: those associated with what has been called the ‘Quantum Revolution’ (quantum computing, cryptography, etc.)

Along with his colleagues at La Salle’s Observatory of Quantum Technology, they have attempted to think through the potential impact and development of sophisticated new technologies using the concept of ‘affordance’; that is, the degree to which a derive may or may not allow a plurality of users.

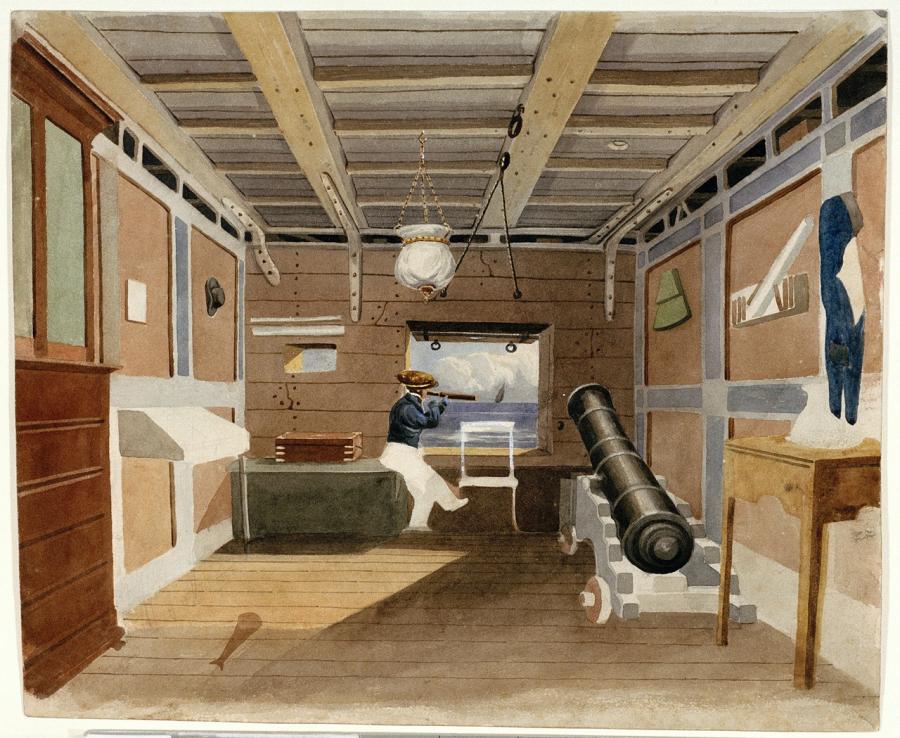

In order to think through the utility of this concept, he has thought about what the term ‘affordance’ might have allowed me to explore in my research into 18th and 19th century timekeepers: Dr. Phillips thinks the place to start would be the object themselves (see below). After a short period of trials in the 1760s, the basic design of mechanical timekeepers for use at sea was standardised: spring-driven (for the escapement) and transported/used in a wooden box. The degree of ‘affordance’ of timekeepers as objects was in many ways quite limited: they were kept in expensively-made boxes and sent on voyages with a specific set of instructions about how they should be used.

This suggests to him that alongside the concept of affordance – those possibilities for use inscribed in the device itself - the work of analysts must also pay attention to – and account for- the ways in which social groups respond to devices and incorporate them within their own set of practices and interests. In this way, the sociological concept of ‘accommodation’ seems a particularly useful complementary term. Accommodation is used by sociologists to mean the ways in which social groups rearrange themselves in order to cope with potential conflict or infringement.

In the case of timekeepers, the intended use may well have caused profound social conflict on a shup, however, strategies were found to overcome this and to manage, as best they could, both the demands of a shup and the demands put of ships by their backers.

Over the course of the next few years, Dr. Phillips looks forward to exploring the relationship between affordance and accommodation of much newer ‘quantum’ technologies, alongside both his students at La Salle and his colleagues at the Observatory of Quantum Technology.